COVID-19's toll on youth's careers

India is home to one-fifth of the world’s youth. Crores of young people are working to build a life for themselves, and lakhs are poised to enter the workforce every month – a process that the COVID-19 pandemic unsettled.

In 2021, Medha conducted a survey with over 7,000 alumni to understand how the pandemic affected young people’s careers and education in Medha’s communities. They had contacted over 12,000 Medha alumni in UP and parts of Haryana and Bihar. Our reflections are based on answers of the 7,035 who responded, of whom 57% are women. The median age was 21.7 years, as most participants were in the 18-25 age group.

The big question

Anjali is an engineering student from a village in U.P. In her family of six, only her father has a smartphone – one with a faulty camera that tends to heat up quickly.

With exams being online during the pandemic, Anjali had to borrow three phones so the invigilators could see her on video. She needed one phone for internet, another for good video quality, and a third for backup in case her phone heats up and switches off!

On the day of her machinery exam, Anjali had to return one of the phones to her neighbor, who needed it urgently. With 10 minutes to her exam, she ran to find someone else in the neighborhood who could lend her their precious phone. Under this stress, she could hardly focus on answering the questions and felt she had let herself down.

Anjali’s story is only one example of the difficulties students all over the country had to face in the pandemic. It illustrates how the simple act of being online is a privilege for young people at a critical point in their careers.

The story made us wonder: if a B.Tech student like Anjali had to go through such debilitating tension before an online exam, what about other young people with fewer resources or less digital know-how? Ultimately, the question is, who really got to participate in education and work during the pandemic? We answer the question based on key insights from the survey below.

Having your own smartphone

We may all have had issues working online or connecting to the Internet during the pandemic. However, our survey revealed systemic patterns about who was able to participate in online work.

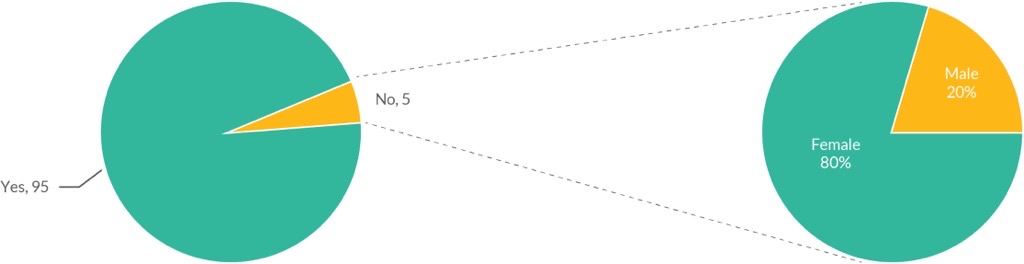

Our experience at Medha is that most alumni use smartphones rather than laptops to access education and career opportunities. However, as in the rest of India, the survey showed that men were significantly more likely to own a smartphone than women: among the 5% who did not have a smartphone, 4 out of 5, or 80%, were women1.

Our experiences in Medha programs like Swarambh (which supports freelancing as a career option for young women) also explain the above quantitative findings.

At the start of Swarambh before the pandemic, Medha encouraged using smartphones to improve digital literacy. However, parents were typically not supportive of their daughters owning a phone. Their reasons reflected norms about what women are permitted to do or not do in many parts of India. These included concerns about privacy, interaction with strangers, and vulnerability to harassment.

However, post the pandemic, Medha faced less resistance (if any) from parents towards their daughters owning and working with smartphones. It indicates a small but significant social shift around young women’s phone ownership.

Getting online

When looking at the problems in getting online, we found that one-third of the alumni (~33%) surveyed had internet issues2. And 18% of internet access issues were due to economic reasons such as insufficient funds to recharge the phone.

Difficulties in phone and internet access fell along the lines of existing socioeconomic inequality: alumni living in urban areas (vs. rural), who were men (vs. women), and who belonged to General Category (vs. SC/ST or OBC) were more likely to own a smartphone and less likely to face internet issuesa.

In a population where the phone in your hand is the primary way to build your career, we repeatedly see that ‘real-world’ inequities trickle into online spaces.

Making the most of digital resources

Having a phone and internet access were essential to participating in work and education during the pandemic. However, we were also curious about the extent to which young people were able to use digital resources.

So, we asked our alumni an open-ended question about what skills they wanted for their careers: more than one-third of alumni said they wanted essential computing or digital literacy skills. These included basic operating functions of a computer, like Microsoft Office, and other things like writing emails, filling out forms online, using social media, or even navigating phone applications.

Beyond questions of digital access, a growing body of literature indicates the losses in learning due to online education. Virtual classwork, as in the pandemic, can lead to poorer academic performance, especially for those already marginalized academically or socially.

In our conversations with educators on campuses, we found it is common to welcome the shift back to offline learning. But, as a government teacher from Varanasi shared:

Vapis kaise layenge? How will we bring back [the students to the academic level they need to have achieved]?

Coping with multiple life stressors

Career-building is just one of the many aspects of life that COVID-19 disrupted. Young people also had to absorb the devastating effect of the pandemic on the health, lives, and livelihoods of their families and communities.

Neha is pursuing her B.A. in Gorakhpur to achieve her dream of being a teacher. After her father’s passing, her mother took on her first job to support the family and had to move out of Gorakhpur. Despite being isolated and facing the challenge of studying online in the lockdown, Neha (the eldest) also had to take care of her younger siblings.

In addition to health and personal loss, economic survival was a constant worry among many Medha alumni. A third of the alumni said the pandemic negatively affected their family’s financial situation.

Preeti (name changed) is a recent polytechnic graduate from Lucknow. Her family ran a small shop, and their financial situation had been precarious. The pandemic pushed their existing economic difficulties into a crisis. To this day, Preeti remains terrified of a lockdown returning because she doesn’t know how her family would survive. She shares:

Dukan band… mummy ki health kharab…Mujhe to bahut dar lagta hai ki pandemic ki situation nahin honi chahiye, lockdown to bilkul nahin aani chahiye…dar lagta hai, without job agar lockdown hoga to bauhat problem hone vaali hai…

(The shop closed.. mummy suffering from health issues… I am afraid. We shouldn’t have a pandemic situation again, and definitely not a lockdown. I am scared that without a job, if we have a lockdown, [my family] will have serious problems.)

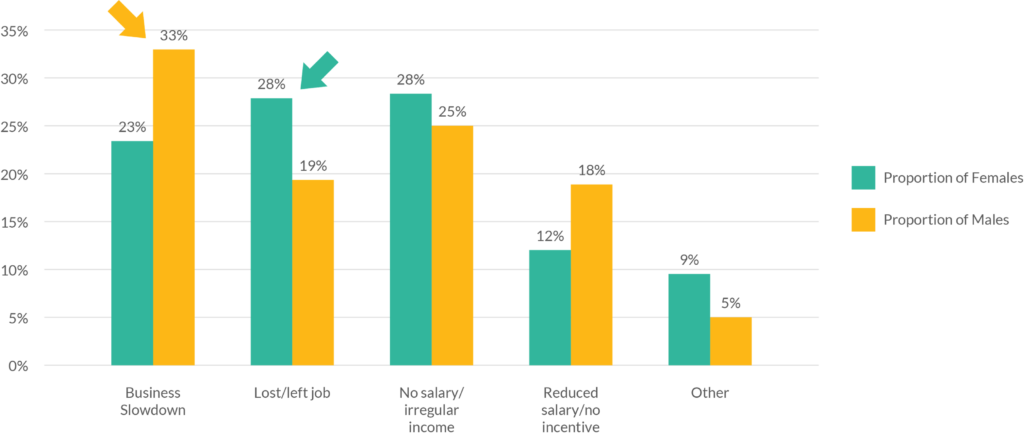

Economic and career insecurity was compounded for Medha’s working alumni as well: almost a third of the working alumni said that their job or business had been negatively affected by COVID-19. The effect3 ranged from business slowing down and salary reduction to losing jobs or livelihood.

Looking back

For young people, passing a competitive exam, getting admitted to an institute, or finding a decent job can be intensely stressful events because they are game-changing moments in one’s career.

The pandemic added additional issues to a young person’s life – Will I have internet for this class? Will my phone work okay during my exam? Will my family member stay well even though their job exposes them to COVID? What happens to my career if the pandemic continues?

Crises like the COVID-19 pandemic are not new. However, part of the tragedy of these critical moments lies in our collective failure to learn from the past and these crises as they unfold. This failure to learn is why, while the digital economy opened up a world of opportunities for youth, wide inequities and exclusion persisted in online spaces, as illustrated in Medha’s survey.

Looking forward

If we want to learn from the past and move forward, we must face a few questions – what is the cost we will bear as a society for the losses young people have faced in their careers in the pandemic? And how will we find meaningful ways to offset these costs?

We don’t have to look too far for an answer. Amidst adversity, a few young people have created work opportunities for themselves and hinted at how they can be better supported.

Neha, whose story we discussed previously, used her skills as a trainee teacher to offer free classes to children who were losing out on social, emotional, and academic learning during the lockdown. Vaishnavi, a 3rd-year B.A. student from Gorakhpur, converted her passion for crafting into an Instagram business.

The world is increasingly online, which is excellent because it makes knowledge, resources, and opportunities potentially more accessible. However, that access will not be equitable on its own. We must improve device ownership and digital know-how in under-served communities so that youth everywhere (like Vaishnavi) can learn new skills and use online resources to build their careers.

As we celebrate being back on campuses and workplaces with the hope for ‘normalcy,’ we must remain conscious of the pandemic’s toll on young people’s lives and careers. And with this recognition, we must find ways to address the setbacks.

a. Results are from logistic regression, variable significance at p>=0.005; controlling for smartphone ownership (N=6,950) and internet issues(N=6,943) for highest qualification and age (continuous).

All views expressed in this story solely belong to the author(s).